⚠️ Note on Methodology:

This analysis includes only original first-party games developed and published by Sony-owned studios at the time of release. Remakes, remasters, and re-releases (e.g., TLOU Part I, Uncharted Collection) were excluded to maintain consistency across generations.

Over the course of three console generations, Sony has established a mark for some of the most refined and critically acclaimed first-party titles in gaming. With their flagship franchises including Uncharted, God of War, Spider-Man, and The Last of Us, PlayStation branded themselves with record-breaking exclusives.

However, now that we are reaching the midpoint in PS5’s lifecycle, one striking change emerges not in quality but quantity.

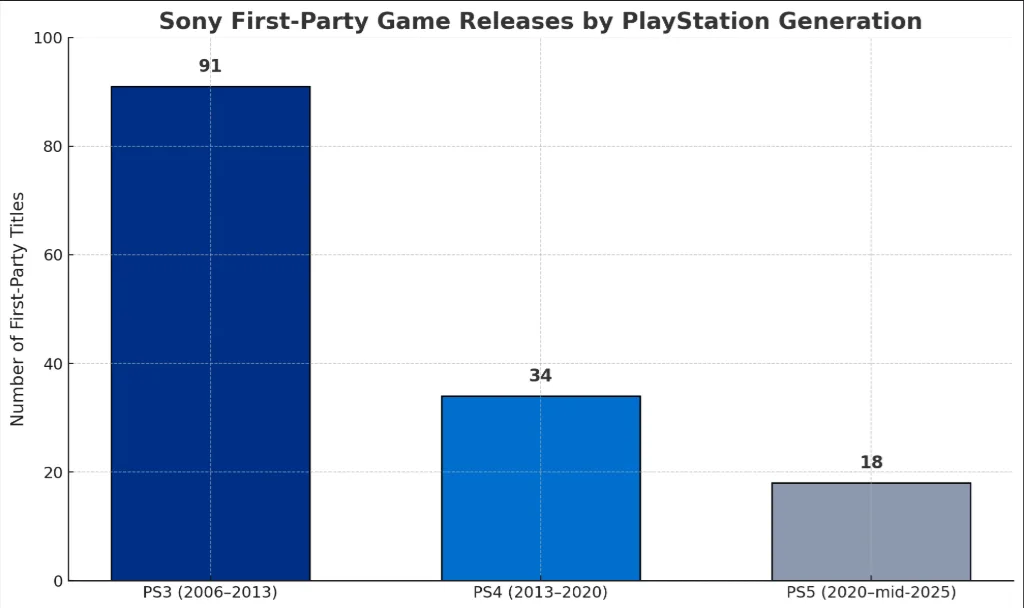

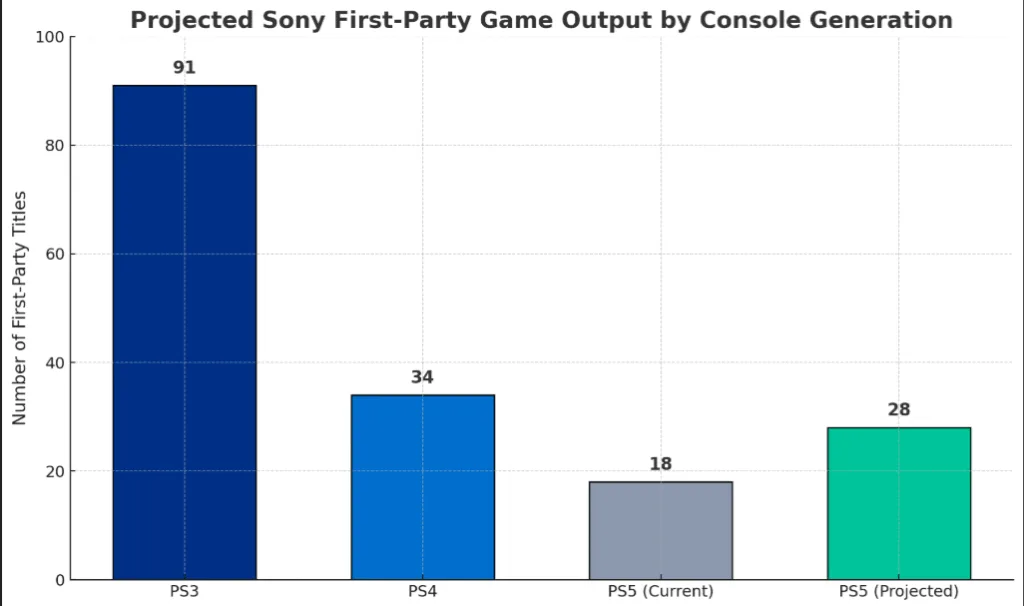

We will analyze the data surrounding Sony’s first-party titles for the PS3, PS4, and PS5 generations. What stands out is not only a decrease but rather a sharp downward drop in the number of games produced by Sony-owned studios. With documented release dates and timelines supported by studio ownership data, this isn’t just bias—there’s solid evidence demonstrating change.

The narrative unearthed describes how Sony’s strategy has shifted over time—and why it is happening.

PS3’s Peak First-Party Output

The PlayStation 3 era (2006-2013) started a bit shaky with high price tags and early confusion, yet Sony soon turned things around and filled the system with remarkable games.

During those seven years the company rolled out 91 true first-party titles built entirely by its own studios. Big crowd-pleasers like Uncharted 2, God of War III, and The Last of Us sat alongside smaller, creative gems such as Echochrome, Puppeteer, and PixelJunk Eden.

What really set that generation apart was the wide mix of projects, not just the sheer number. Teams at Sony Japan Studio, London Studio, and Santa Monica jumped in together or lent a hand to let even the boldest ideas see the light.

Players could choose from cinematic, story-driven campaigns or quirky download-only experiments that often tried something new, whether in art style, mechanics, or tech.

Around its busy stretch from 2007 to 2010, Sony averaged well over a dozen first-party releases each year, spilling into nearly every genre and budget bracket.

That open-door approach made store shelves feel lively, as fresh trailers and announcements popped up in short order-a stark contrast to the steadier, more deliberate schedules newer consoles lean on today.

PS4’s Streamlined Slate

When the PlayStation 4 launched in 2013, Sony gently changed how it thought about its own studios. Yes, the PS4 quickly became the bestseller of the generation and earned rave reviews, but the flow of first-party titles slowed down noticeably.

During the entire PS4 era from 2013 to 2020, Sony put out only 34 true first-party games. That number is down more than 60% from the busy PS3 years. The 34 games we did get Bloodborne, Uncharted 4, Horizon Zero Dawn, and God of War (2018) among them-show how high the quality bar has risen, yet they also underline a clearer pattern: fewer games, much bigger budgets, and longer development times.

That “fewer, bigger, better” motto soon became part of Sony’s brand story. Series that started in the PS3 days moved up to tent-pole status, while other projects were quietly retired. Teams like Japan Studio, which once spun out quirky and mid-range titles, were shrunk or closed altogether. Because of these changes, we saw the launch calendar fill up with just 1 to 3 first-party releases each year in the PS4’s early seasons.

Even though average Metacritic scores keep climbing, the range of games has shrunk. We don’t see as many wild surprises anymore because Sony now focuses almost entirely on big, high-budget experiences that are polished, moving, and technically sharp. The price for that shift is clear: We’re getting fewer games each year, experimentation has taken a back seat, and we have to wait longer between the headline releases.

PS5 and the Ongoing Decline

When the PlayStation 5 arrived in late 2020, Sony had already committed to a bold release plan: drop cinematic, story-heavy blockbusters, polish beloved franchises until they shine, and market each title like a Hollywood premier. The gamble paid off in a big way, scoring both rave reviews and record sales, but it also shrank the overall number of games coming out of its studios.

By the middle of 2025, only eighteen full first-party titles had landed on PS5. Yes, that list includes heavy hitters like God of War Ragnarök, Horizon Forbidden West, Gran Turismo 7, and the newly launched Spider-Man 2. Even so, if release schedules stay the same, the current console generation may wrap up with no more than thirty first-party games—analysts are calling it 28 based on pipeline leaks.

So we’re not seeing a momentary slowdown; Sony is consciously redefining what it sees as its bread-and-butter output.

That shift isn’t about poor planning or running out of money—by all accounts the opposite is true. Each new blockbuster now commands a giant budget and carries enormous risk, requiring five to seven years of steady work. Still, when you stack a possible 28 PS5 releases next to the 91 titles that rolled out during the PS3 years, the drop in overall volume hits harder than seventy percent.

What’s closing the empty spaces? Remakes. Directors’ cuts. Updated PC versions. A steady move toward live-service titles and cross-platform play. Sony no longer has to fill every slot on its console with first-party releases, like it did during the PS3 days—its business now reaches well beyond the hardware.

For older fans who remember PlayStation’s wildest, most creative period, that change feels bigger than simple numbers. It touches the very heart of who PlayStation thinks it is.

| Category | Impact on Output |

|---|---|

| Longer development cycles | 🔻 |

| Blockbuster-focused strategy | 🔻 |

| Studio closures & restructuring | 🔻 |

| Delayed acquisitions | 🔻 |

| Focus on live-service & PC markets | 🔻 |

| More remasters vs. new IP | 🔻 |

“fewer, bigger, better”

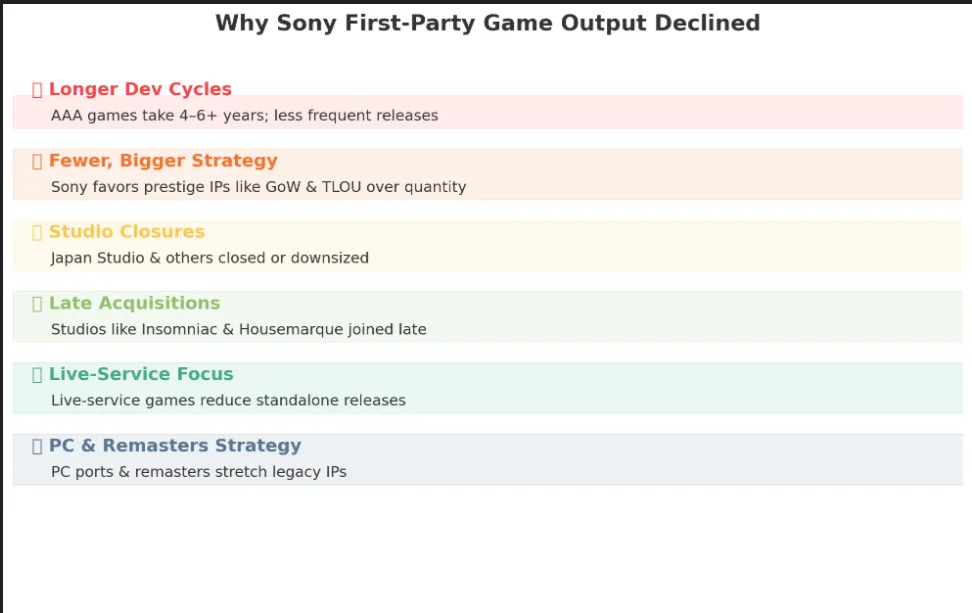

Sony’s drop in the number of in-house games isn’t just luck; it’s a careful, layered plan that lines up with wider changes in gaming and within PlayStation itself.

Game-making is now slower and far trickier than it used to be. Blockbusters like The Last of Us Part II or Spider-Man 2 aren’t turned out in 18 months; they can take four to seven years, often with hundreds of people spread across several studios. The higher the quality goal, the longer the clock runs. That naturally limits how many titles a single studio-or even a whole console maker-can release in one hardware cycle.

So PlayStation leaders lean on a clear “fewer, bigger, better” rule. Instead of flooding shelves with small, mid-range experiments, Sony now puts its chips on proven franchises. God of War, Horizon, Spider-Man, and The Last of Us have grown into multi-game, cross-media powerhouses. With sales often topping 10 million copies and shelves lined with awards, Sony sees a better return in climbing up than in spreading out.

Back in the PS3 days, Japan Studio and London Studio, along with smaller regional teams, spent their time making weird and creative games that stood out. Over the years most of those studios closed or merged with bigger outfits. Sony then decided to pour more support into well-known powerhouses like Santa Monica, Naughty Dog, Guerrilla, and Insomniac, teams that now chase blockbuster, movie-like experiences. Because of that shift, the line-up became smaller, more similar, and leaned heavily toward action and drama.

Today, Sony thinks beyond just selling consoles. Big names like Horizon Zero Dawn, Spider-Man, and The Last of Us have all done solid numbers on PC.

At the same time, the company is pushing live-service titles with Bungie at the helm and other partners lending a hand. These games are built to grow over years, not be replaced every season. Because of that long-term plan, Sony no longer needs a steady flood of new first-party hits just to keep players logging in.

There’s clear money sense behind the move. Making a big AAA game can burn through cash fast—reports say Spider-Man 2 alone ran past $300 million for development and marketing.

By betting on a handful of tried-and-true blockbusters, studios hope to lower that risk and stay in the black. Plus, with steady income now flowing in from PS Plus, third-party royalties, and new movie and show deals, Sony no longer requires every first-party title to hold up the whole PlayStation brand like it had to in the PS3 days.

Sony once treated its first-party development like an open studio filled with wild ideas and bold experiments; now it runs more like a high-end fashion line that drops a few carefully tailored blockbusters each season. That shift has paid off in awards, record sales, and fans lining up- yet the numbers show that variety, release tempo, and risk-taking have all pulled back.

With new live-service games queued up, more remasters and ports rolling out, and multiplatform projects taking center stage, the picture of Sony’s first-party future feels different, centralized and polished rather than sprawling and surprising. The PS5 is still fresh, so fresh news could yet appear. Still, unless strategy changes soon,two dozen big PS staples per calendar year seem unlikely to return.

If you came of age during the PS3 golden rush, you might miss that steady drumbeat of fun, weird titles dropping unannounced. Quality hasn’t vanished; so much is still world-class. It’s the rhythm, the small-jolt novelty of finding a fresh PlayStation exclusive, and the overall sense of creative freedom and surprise, that blue-sky feeling, that now feels quieter.